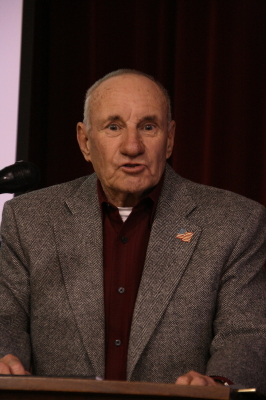

Meet Paul “Pic” Huffman and his wife, Elizabeth. A very photogenic couple, wouldn’t you say? And, I might add, a lovely one–two very nice, warm people who welcomed me into their house near Elkhart, Indiana, yesterday for a conversation I’ve been looking forward to a long, long time.

Forty-five years ago, on the evening of April 11, 1965, Paul and Elizabeth were homeward bound on US 33 when Elizabeth spotted what looked like a column of smoke off to the west. “Look at that smoke,” she told Paul. “Something’s burning.”

“That’s not smoke,” Paul replied.

Pulling the car off onto the shoulder, he grabbed his camera out of the back seat. Then, scrambling out of the vehicle and hooking his leg around the front bumper to steady himself in the wind, Paul Huffman began snapping photos as a tornado moved across the field, broadening and intensifying on its rapid journey toward the Midway Trailer Park less than half a mile up the road.

One of Paul’s photos, taken as debris from mobile homes exploded skyward, became not only the instant icon of the second worst tornado outbreak in Midwestern history, but also what is undoubtedly the most famous tornado photograph of all time. With the emotional impact peculiar to black-and-white photography, Paul’s photo depicts twin funnels straddling US 33 like a pair of immense, black legs. It is a chilling image, instantly recognizable to anyone interested in tornado research or severe weather history.

Researching for a book I’m writing on the 1965 Palm Sunday Tornadoes, I’ve come across several variations of Paul’s story by different writers. The discrepancies have been enough to leave me feeling frustrated. The Huffmans’ account strikes me as integral to a book on the outbreak, and as a matter of both responsible writing and simple respect, I’ve wanted to learn the facts and offer as accurate a writeup as possible. I was delighted last year, then, to learn that Paul would be one of the featured speakers at a Palm Sunday Outbreak commemorative event at the Bristol Museum.

Of course I attended the commemoration, where I connected with my friends Pat Bowman and Debbie Watters (my two “tornado ladies”) and also met Paul and Elizabeth for the first time. It was then that I requested an interview. Now, a year-and-a-half later, I finally got the opportunity.

When I arrived at their house, the Huffmans were standing outside surveying damage to their property from the previous day’s derecho. A small tree was down, a flagpole had gotten blown over, and a lot of tree litter had filled the yard. It seemed ironic that I was meeting Paul and Elizabeth on the wings of another bad storm.

They invited me inside, and we had a great chat that covered a lot more ground than just the tornadoes. In their early 80s, the Huffmans are an engaging twosome with plenty of stories to share. Paul, who served as a reporter for the Elkhart Truth, regaled me with several accounts from back in the day, including a flyover directly over a smokestack of the newly built Cook nuclear power plant, and a humorous mishap on the roof of a quonset hut. But of course, the main focus was his experience with the Midway tornado.

I won’t go into details here because it’s been a long day and I’m tired, and besides, I haven’t had a chance to review the interview tape. But here are a few noteworthy highlights:

* Paul never saw the twin funnels when they occurred. He was too busy snapping pictures, and he saw only the rightmost funnel in his viewfinder. Not until later, when he developed his film in his darkroom at home, did he realize what an unusual image he had captured.

* Among the larger pieces of debris raining around the Huffmans’ vehicle was a car which got flung overhead and landed on the other side of the railroad tracks that parallel US 33.

* The Huffmans never heard any of the tornado forecasts that were broadcast that day. But Paul, working outdoors earlier in that balmy afternoon sunshine, sensed that bad weather was on the way and mentioned it to Elizabeth.

* Ted Fujita interviewed the Huffmans at their house. Paul said that during his visit, Fujita seemed, oddly enough, to be more interested in Saint Elmo’s fire than in the tornado.

Paul’s overall work as a photojournalist won him a number of awards, but I’m sure that he and Elizabeth would agree that it was his one remarkable, serendipitous photograph of “The Twins” that gained him fame, if not necessarily fortune. It is strange to think how an ordinary, down-to-earth man can find himself in the right place at the right time, doing what he was designed to do–in Paul’s case, taking photographs–and wind up having an impact that shapes lives and vocations. It’s impossible to say how many people have been affected by Paul’s powerful and horrifying photo of the Midway tornado, but I know that it has helped to inspire a few notable careers in meteorology and media, not to mention many a storm chaser. It was a treat to finally get to sit down and talk with the man who took that picture, and to enjoy him and his wife not merely for their fascinating account, but also for the fine, intelligent, humorous, hospitable people that they are.