The time has come for me to kick it up a notch on Stormhorn.com with my first video tutorial on jazz. This one is on the augmented scale, a favorite of mine.

I feel a bit presumptuous taking this step, since I’m putting myself out in front of you, my musical readers, in a new way that suggests a high degree of expertise. The reality is, I’m a mostly self-taught saxophonist who lives in a rural, bedroom community of Grand Rapids, Michigan, where you can still drive just a few blocks to find plenty of corn and cows. That said, I know what I know. More important, I’m a perpetual learner, and I like to share what I’ve learned, often as I’m still in the process of learning it. This video tutorial represents my effort to offer you more value by, er, augmenting your learning experience. (Pun intended. Rimshot, please.)

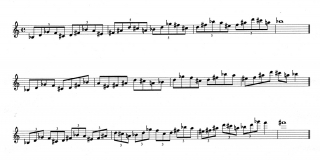

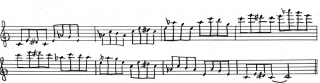

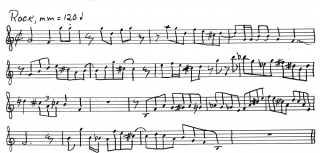

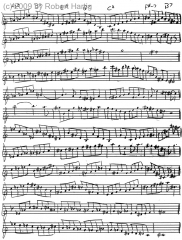

In the Jazz Theory, Technique, and Solo Transcriptions section of my Jazz page, you’ll find a good number of written articles on the augmented scale, complete with exercises, to supplement this video. One thing they can’t do, though, is familiarize you with the sound of the scale. That’s where this tutorial comes in handy. I hope you’ll enjoy it.