Almost two months have elapsed since my last post. An entire winter is now nearly behind me, and with meteorological spring having sprung as of yesterday, my eyes turn once again to the coming storm season.

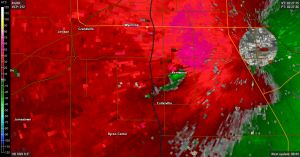

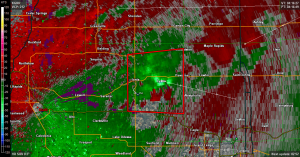

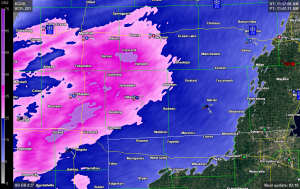

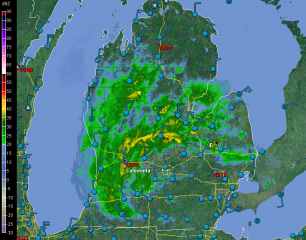

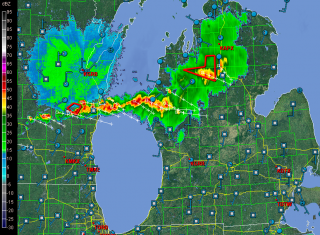

Going through my old radar images, I came upon this one. Click on it to enlarge it, then note the station obs and wind barbs on either side of that fine line west of Minneapolis. That sure looks like a dryline to me, but what’s it doing wandering around central Minnesota like a little lost orphan?

Going through my old radar images, I came upon this one. Click on it to enlarge it, then note the station obs and wind barbs on either side of that fine line west of Minneapolis. That sure looks like a dryline to me, but what’s it doing wandering around central Minnesota like a little lost orphan?

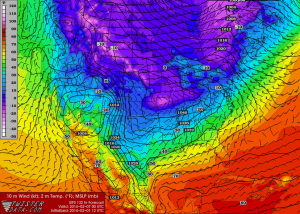

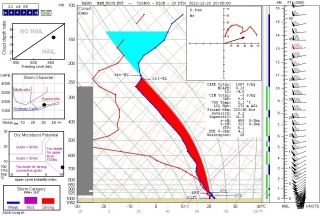

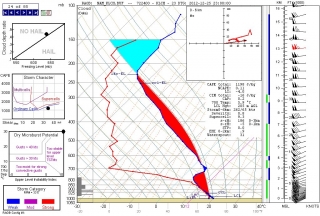

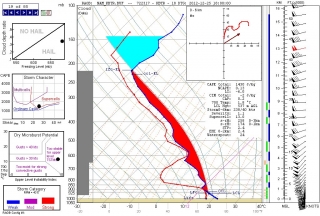

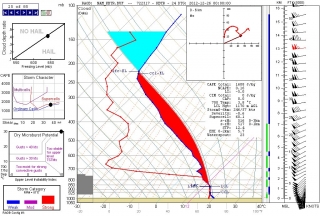

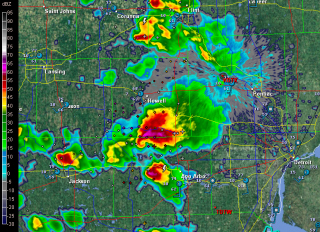

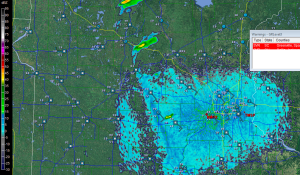

The Great Lakes are not the land of drylines, but we do get them occasionally, and as out in the Great Plains, they can serve as a forcing mechanism for severe weather. Notably, in the 1965 Palm Sunday Outbreak, what Theodore Fujita called a “dry cold front” featured prominently in his analysis of the synoptic conditions. Although Fujita called the air behind the front “cooler,” a look at the station observations reveals that what really characterized the difference on either side of the “front” wasn’t a rapid drop in air temperature but in dewpoints, and a change in wind direction, with surface winds veering abruptly from the south to the southwest.

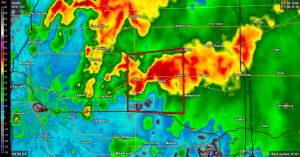

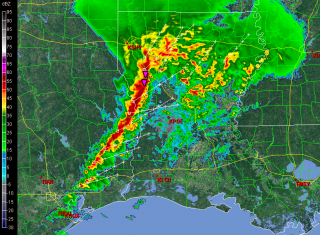

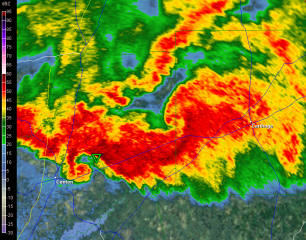

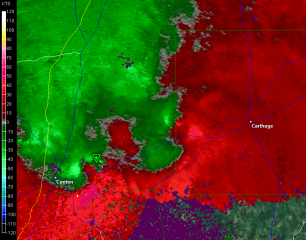

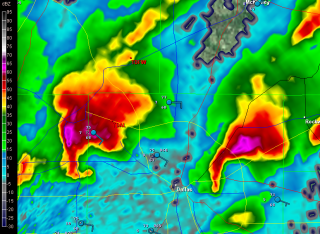

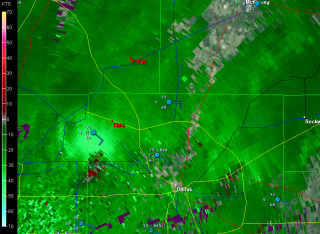

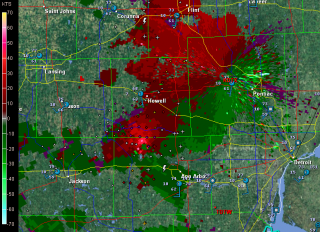

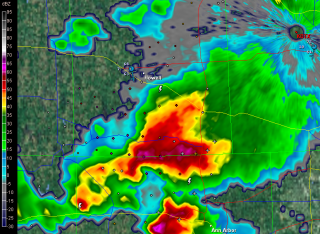

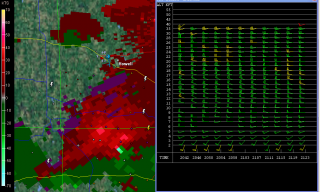

The radar grab shows similar conditions on May 10, 2011, with supercells initiating along a line of strong convergence. Where the southernmost cell is just starting to fire, check out the obs on either side of the fine line. The temperature is the same, 90 F degrees, but the dewpoint drop is as much as 13 degrees. That may not be as radical as what you’ll find in the Texas panhandle, but in the Great Lakes, it’s an eye-opener.

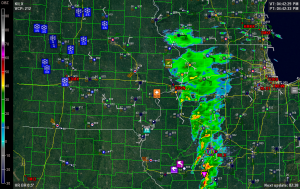

There were tornadoes in eastern Minnesota on this day: May 10, 2011, SPC Storm Reports. The location of the three reports on the SPC graphic leads me to think that the cell I mentioned in the previous paragraph may have been the culprit. With dewpoints in the upper 60s to low 70s, it appears to have had plenty of juice to work with.

For a dryline to occur in the Great Lakes means that a system is potent enough to wrap in dry air this far east from the desert Southwest. That means that a lot of things have fallen into place to create a potentially tornadic setup, including not only an obvious lifting mechanism but also ample bulk shear and moisture, and southerly or southeasterly surface winds. In other words, here in my backyard, a dryline is a red flag that things are about to pop and a chase day is at hand.