Judging from the forecast soundings, it seemed that northern Michigan stood at least a chance of tornadoes yesterday evening. But the storms that first ignited in Wisconsin quickly congealed into a broken line as they crossed Lake Michigan, minimizing their tornadic potential and fulfilling the predictions of forecast models and the knowledgeable heads at the Storm Prediction Center.

I made the trip north regardless of, from my standpoint as a storm chaser, the unpromising prognosis. I hadn’t been upstate yet this year, I was itching for a bit of convective violence in any form, and the thought of simply watching a brooding shelf cloud blow in over the beautiful hills-and-water region around Traverse City appealed to me. Given ample low-level helicity between 200-300 m2/s2, I figured I stood at least a chance of getting some rotation out of a tail-end cell or perhaps a hook-like protrusion. But I was willing to settle for less, which is what I expected and what I got.

I headed north on US 131 as far as Kalkaska. Then, with storms to both my north and west, I decided I’d be better off heading west down SR 72 and meeting the southernmost cells moving in toward Traverse City.

At Acme, I caught US 31 north, and from then on my goal was to find a good place to park and get some pics. That’s easier said than done in a landscape filled with timber. Grand Traverse Bay was almost within spitting distance, and I could see glowering, lightning-laced clouds advancing to my northwest. But, blocked by trees, the clear view I envisioned of a shelf cloud bulldozing in over the bay kept eluding me.

Finally I found myself in Elk Rapids. The town was right on the water; there had to be someplace to park with an open view.

At a stop sign, I edged out prematurely, then tapped on the brakes as fellow chaser Nick Nolte turned off the main drag in front of me. Cool–Nick was here too. I figured I’d find a spot, then give him a call. As it turned out, Nick found me first a few minutes later in the parking lot of the local marina.

“Hey, I just about ran into you at an intersection,” I told him.

“That was you?” he said. “Jerk!”

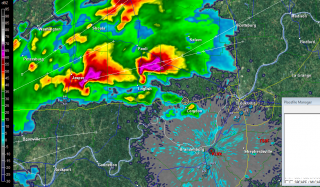

Our location was probably as close to ideal as possible, given the lay of the land. The cell to our north blew past, but the radar indicated a bow echo making its way directly toward us. I’d never have guessed from the bland-looking sky to the west. But in a few minutes, storm features began to emerge from the nondescript grayness like an old Polaroid photograph developing. A shelf cloud was advancing across the bay, growing more distinct by the second.

Nick hopped out of his car and tripoded his camera. I opted to go hand-held–not the best approach, but in this case a practical one. But my camera gave me grief; the shutter wouldn’t operate, and by the time I remembered that I needed to turn off the auto-focus, the shelf cloud was overhead. Nuts. I snapped the five shots you see below, then got in my car as the rain and wind descended in earnest.

The marina was right in the belly of the bow, and for a few minutes, I enjoyed a nice blast punctuated with lightning and commented on by thunder. Then the line moved off to the east. Nick and I decided to try and reposition in hopes of intercepting the southern end, but our attempt was futile. We ended the chase and grabbed dinner at a Big Boy restaurant in Kalkaska.

This time of year, any storm is a good storm–not that I’ll normally drive 175 miles just to see a bow echo, but I don’t need a Great Plains tornado to make me happy. After multiplied days of remorselessly gorgeous weather, a boisterous round of lightning and thunder always gladdens my heart and gets a shout out of me.

ADDENDUM: The tail-end cell, which had consistently displayed a hook-like appendage and shown an inclination to turn right, went on to produce an EF-1 tornado at a golf course near Roscommon, forty miles east-southeast of where Nick and I grabbed dinner in Kalkaska. The low-level helicity delivered after all. If the storms had been discrete, I suspect we’d have seen a few more tornado reports.